STORIES

2020

BY 开伦

BY 开伦

Magdalena was an artist. It was made obvious by her short hair that was tousled with gel so it would hold its perfectly disheveled appearance, and finger tattoos that included a feather, an infinity symbol, an arrow, a rose, an anchor, a crescent moon, a broken heart, a semicolon, and a triangle. She still had one empty digit she planned to fill up with a cross, as she was spiritual but not religious.

Unlike her mother, Magdalena was a professional. Her mother spent her spare time making Bob-Ross-esque paintings of flowers and landscapes meant to match the furniture more than to elicit any critical response. Purely aesthetic with no real intellectual value.

Unlike her mother, art was not a hobby for Magdalena, it was a career, and her paintings were "fine" in the cutting-edge contemporary sense. Giant, abstract canvasses consisting of one somber, oppressive color meant to evoke the societal oppression she was living under. Magdalena was able to pay for an apartment in New York with her art, and this validated and reassured her that she was meeting whatever the ambiguous standard of "professional" was in the contemporary gallery scene.

Magdalena had stuck a wet finger in the air and determined that the trends of the art world were blowing toward issues of identity. Namely gender, sexuality, class, and race. Magdalena was white, so that excluded one category. She was also an only child of wealthy parents who footed the bill for SFAI, so that barred her from another. But she was a woman, and only mostly straight, which allowed her to comment on two of the demographic issues that the NY elite liked to see represented in galleries. The reassurance and self-esteem that came with her initial success were eradicated, however, when Magdalena went to visit some friends from art school in San Francisco.

The couple managed a production pottery studio in the bay area. They were both immensely skilled at their craft, having studied traditional ceramics in Japan, and owned one of the few anagama kilns on the west coast– an ancient method of firing in which flames and ash from piles of dried timber are blasted through chambers dug out of a hillside, vitrifying the clay within. Magdalena held a slight disdain for this couple's adherence to traditional and functional art, but it only manifested in a subtly patronizing tone when given a tour of the studio, which the couple picked up on but ignored.

On the last day of her visit, having more-or-less run out of things to talk about, Magdalena decided to go to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art while her friends were occupied at the studio. She saw some Picassos, some Wols, some Warhols, but nothing that really engaged the capacity for critical thinking her parents had paid so much money to develop. These ideas and aesthetics were old, and she was interested in the new.

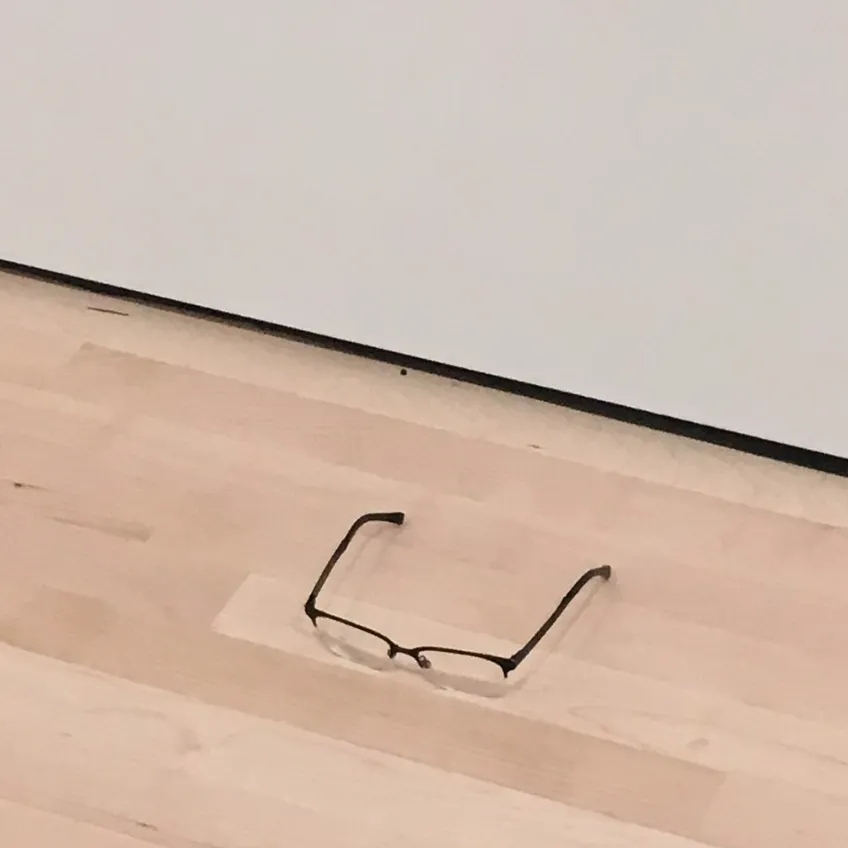

She was ready to leave, feeling dissatisfied but simultaneously self-satisfied that none of the exhibitions had really challenged her when she saw a pair of reading glasses sitting on the floor in front of a blank wall. She bent down to get a closer look. They appeared to be a normal pair of black reading glasses, but their implication in a museum setting was potentially profound.

Was it a statement about the perception of art as viewed through the lens of the museum? Possibly something to do with the metaphorical and contextual assistance we use when viewing art? The glasses were juxtaposed with a painting by Magritte, so maybe it was a comment on the attempt to study surrealism with the conscious mind when surrealist values could only really exist in the subconscious. Whatever the intention, this work was significant.

Magdalena played this game of mulling over possible intentions for another minute before she noticed two teenage boys staring at her from across the room trying to restrain their sniggering. They quickly turned away when she looked at them. Fucking teenagers, she thought. How much of what was in this museum could they possibly comprehend?

But when she got bored of playing this game and started looking for the description, the boys started to laugh openly. She stared them down. Again, they looked away but failed to keep their composure. Magdalena ignored them and went back to looking for the description, but when she was about to give up, a chaperone walked in and told the boys it was time to meet outside for lunch. One of the boys, who now looked a little embarrassed, walked over and picked up the glasses while the other spewed that mocking laughter that teenagers are so good at. The chaperone quickly hid his amusement with an apologetic look, and they left Magdalena to marinate in the realization that she had just been pranked.

But for Magdalena, it was more than a prank. It was the obliteration of her self-esteem. The image of herself as the edgy intellectual she had carefully maintained was seared by the light focused through the lenses of this teenager's antics. The education she received, the criteria with which she had created her own art, the contemporary values, terms, and standards that she relied on for validation were spontaneously ripped away from her, and the separation anxiety was too much. She needed to leave.

The Uber driver was playing smooth jazz on the way back to her friends' place. Kenny G or someone who sounded like him was the soundtrack of Magdalena's neurosis, which she attempted to keep hidden from the driver by staring at the blank screen of her phone. She sat in the back of the car, trying to mentally redefine her art in a way that kept it from falling into the same category as those reading glasses, but the sound of that teenager's laughter mixed with tenor saxophone reverberated in her head and overwhelmed all other thoughts.

When she got back to the couple's studio, Magdalena headed straight to the anagama. She crawled through the open hatch in the ground, down into a cramped cave filled with shelves of exquisite pottery– formidable yet simple forms shaped by years of practicing and honing of the craft, waiting to be transmuted from dried clay into objects of superb beauty and utility.

Under the packed earth, Magdalena's disdain for these vessels twisted into hate. Starved for validation, she now struggled to find any beauty or utility in the monochrome canvasses of her own art and came to the deeply distressing conclusion that they essentially filled the same decorative function of her mother's kitsch landscapes.

With this realization came a blistering, jealous resentment of the pots that surrounded her. They seemed to be mocking her, taunting her like those teenage boys. They sat there on the shelves, confident in their tradition and their history and their magnificence, and exuded the same disdain for her as she previously had for them. But they were also vulnerable. So Magdalena, in a frantic attempt to nurse her mutilated ego, picked them up and smashed them on the ground, one by one.

When the couple found her, she was quietly sobbing amongst the shards. They helped her up out of the kiln and gave her some water in a bowl. It was surprisingly light, and for the first time, she took notice of the random constellations of wood ash and glaze interacting with one another, like viewing a distant galaxy. The couple quietly suggested that she stay another few days to help them with the next firing. She agreed, knowing they could have asked her for much more. So for three days and three nights, Magdalena stoked the kiln with piles of cedar, pine and cypress. Every time she brought her face close to the flames emanating from the open mouth of the anagama, she could feel her pretensions burn away, little by little.