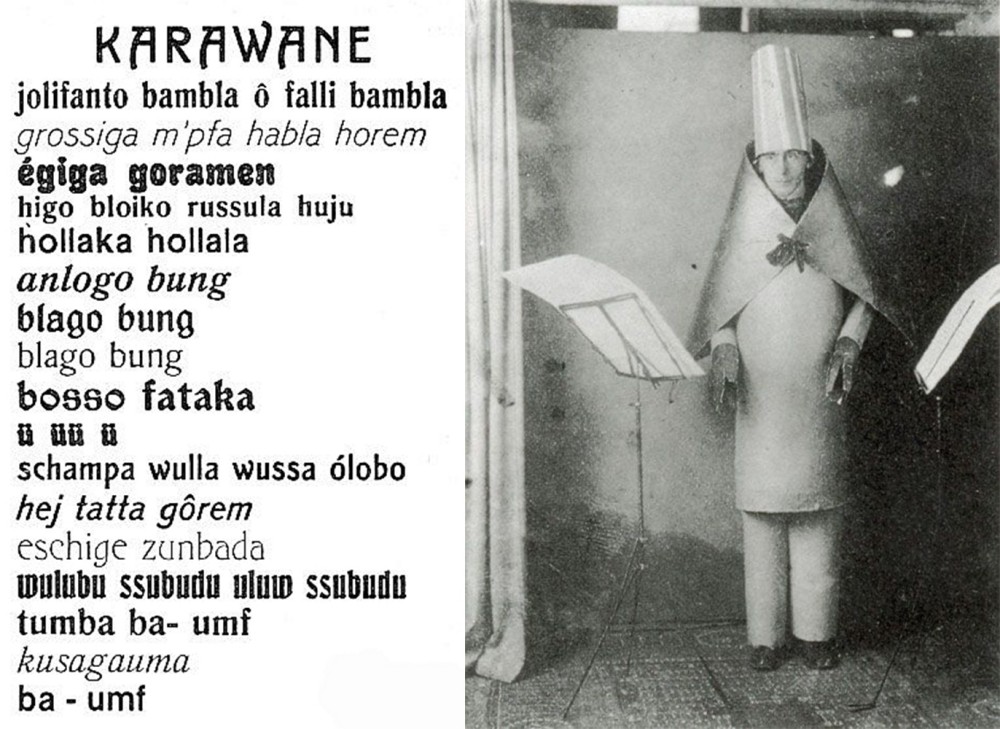

Gustave Courbet - The Stonebreakers, 1849

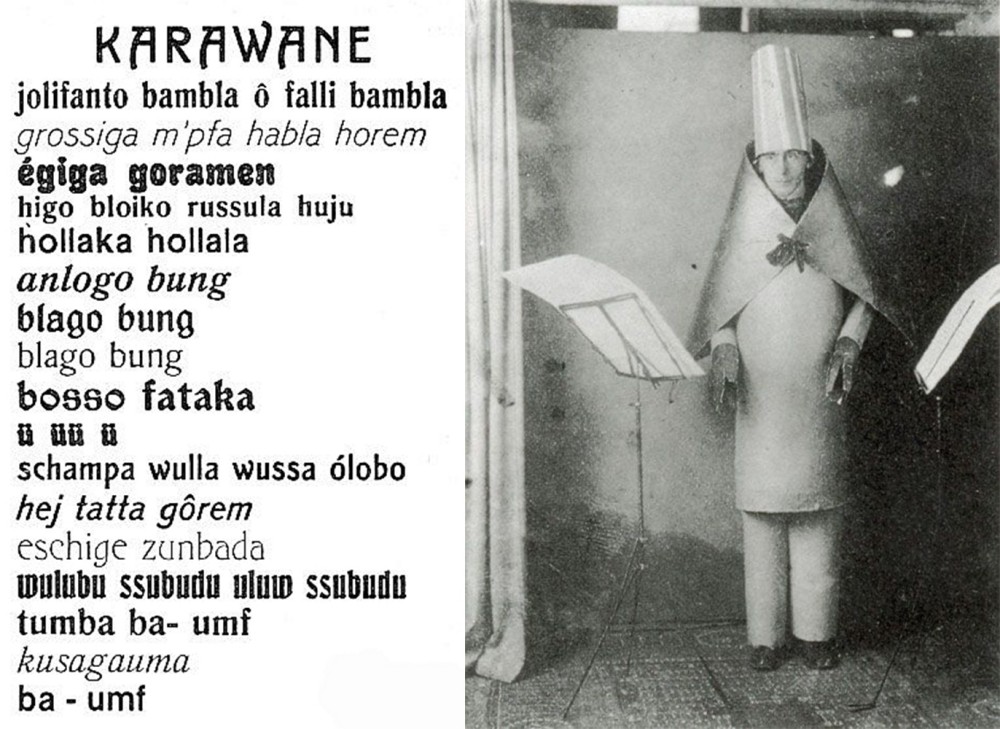

Hugo Ball - Karawane, 1916

Closely related to the idea of offense is that of “transgression.” Because of the conceptual proximity of transgression to offense as it applies to the arts, it is worth distinguishing the two, as the history of artistic transgression has been relatively well established. In order to arrive at a working concept of offense, it is worth examining and comparing the established concept of transgression. As elaborated by Michel Foucault in A Preface to Transgression, transgression is the act of crossing a limit. He writes:

Transgression is an action which involves the limit, that narrow zone of a line where it displays the flash of its passage, but perhaps also its entire trajectory, even its origin; it is likely that transgression has its entire space in the line it crosses.4

Although artistic transgression has arguably existed for as long as art has, to illustrate the modern development of this concept, we can start with French Realists like Gustav Courbet. Works like The Stone Breakers were created as a form of social commentary and political protest, depicting fatigued peasants consigned to menial labor. In the early 20th century, during the Dada movement, the overt and explicit political message of social realism was gradually replaced by a form of formal transgression meant to act as a placeholder for politics,5 as seen in works like Hugo Ball’s Karawane, in which he read incomprehensible poetry dressed in a crude lobster costume in an effort to preserve his communist ideals in nonsensicality.

The shift from explicit social commentary to para-political formal transgression was completed and codified in modern art, with critics like Clement Greenberg arguing that the formal experimentation and transgression by artists like Jackson Pollock was essentially an aesthetic substitution for social revolution.6 Now, it is possible to transgress primarily against the “critical orthodoxy” of formalism, as stated by the critic Jeffrey Weiss when writing about the haphazard scrawls of Cy Twombly.7

Herein lies one of the central limitations of transgression as it applies to the proposed concept offense. It is possible for an artist to transgress exclusively within the boundaries of formalism, the transgression in this case being contained within the aesthetic qualities of the work itself. Offense, as it is generally understood today, has a connotation that is more personal. It is a social violation, not a formal one. Even in cases where formal transgression is used as a placeholder for political transgression, the act itself is ultimately formalistic. For example, one could take issue with Paul Signac’s anarchist philosophy, but it is harder to imagine that one would be personally offended by the pointillist style he developed to support his politics despite the fact that pointillism was aesthetically transgressive at the time.8

Even when a work is overtly political, political statements do not guarantee offense. Today, political protest against power structures is so much the norm in western contemporary art that it borders on banality. As the critic, Robert Hughes, states in Culture of Complaint, “The political art we have in postmodernist America is one long exercise of preaching to the converted.”9 Today, making work that comments on some form of oppression is more of an expectation than a violation.

Again, Foucault states that transgression is “the act of crossing a limit.” Actions require actors, and it is this association that has tied the idea of transgression to the transgressor. Transgression lies in the action of the artist, which is why, generally, the artist transgresses with the intention, or at least awareness, that they are doing so. As transgression is thought of now, being transgressive does not require an audience; the act of transgression can be contained entirely in the space between an artist and their work, as crossing a line, whether it be social, political, or aesthetic, does not necessarily require a witness.

Many of the contemporary issues that artists face, however, do not result from the act of creation (and possible transgression), but from the viewer’s response to the act of creation. While transgression is contained in the action of the artist, it is more practical to think of “offense” as being contained in the response of the viewer. The artist can intend to offend, or not, but it is ultimately up to the viewer to decide whether or not they feel offended. In that sense, “offensive” work derives its label from the response of the public. Though the intention of the artist is important and should be factored into the evaluation of the artist's work, intention alone cannot dictate the subjective response of the viewer.

This is not to say that transgressing and causing offense are mutually exclusive. It is certainly possible to transgress against social standards as one can with aesthetic standards. These two concepts can bleed into each other in, for example, the late communist manifestos of dadaism that propose an epistemological justification for shocking the bourgeois viewer into class-consciousness by transgressing against both the aesthetic and societal values of the time.10 Whether or not such an awakening has ever actually resulted from viewing artwork is debatable, but this value differs from the proposed concept offense in that offense aims towards no such epiphanies.

If anything, it is well-established in the field of psychology that offense has just as much of a capacity to entrench people in their beliefs as it does to expand said beliefs.11 Instead of offense affecting change on the level of individual awakenings from viewers who encounter the offending work, its potential value can instead be found in the light it shines on our collective beliefs. It tests, and sometimes infringes, the limits of our collective sensibilities, and in doing so, it helps clarify what these sensibilities are and whether they are worth reconsidering. This consideration can take place on the scale of those who encounter the work and feel offended, those that hear of the resulting controversy and the issues that are involved, and even those who experience the institutional and policy changes that come as a response.

Offense has the ability to focus public attention, but, as the following artworks illustrate, such attention does not always result in desirable outcomes. In order to flesh out the concept of offense, it is worth examining both the intention of the artist and the reaction of the viewers when determining if the offense is “justified.” These case studies elaborate on the role and value of offense in contemporary art, but also function as examples that illustrate the boundaries of justifiable offense and the consequences, both positive and negative, that offense elicits.